Euro nymphing is where it’s at. Everyone loves it. Why try anything else? But, in the words of the comedian Jimmy Cricket, “Wait, there’s more!” Trust me, there’s so much more to nymphing than the long-leader method.

In fact, to catch lots of grayling in winter, I’d recommend the now mythical method that first came to our attention at the World Fly Fishing Championships on the Welsh Dee in the mid-1980s. Then, the Czechs blitzed everyone with their approach. It was close-quarters fishing and nothing like anything we’d seen in the UK.

Czech nymphing, in a nutshell, involves trundling heavily leaded flies on a short tippet, 4ft-5ft, past your feet while wading in deep, fast-flowing rivers. The Czechs used it as the most effective way of targeting the large numbers of grayling in the Dee. It was and still is much more effective than Euro nymphing (for grayling, anyway). But it seems many new fly-fishers find it old-fashioned; obsolete.

They seem unaware of how effective it is, especially in winter. Most prefer the Euro method of lobbing a long length of tippet 20ft upstream and watching an indicator to see if it plunges to the water’s surface — a take — as their flies are swept downstream.

Czech nymphing, or the rolled nymph, known in Scotland, the North of England and most of Wales as bugging, is fuss-free and easy to learn. However, even this simple style has been improved over the years. It must have been the late-’90s when one of my friends, Paul Davidson, a thinking angler, made an amazing discovery that improved his catch rate while bugging for grayling.

In conversation with friends, he learned how braided line was being used by the North East’s leading sea-anglers. This super-slim, no-stretch material cut through the sea; the tide’s ebb and flow had much less influence than it did on mono. The highlight for Paul was that takes could be registered on the longest casts; anglers were able to feel everything when using braid. It raised their game, and fishing is all about marginal gains.

Paul figured that if takes could be felt 100 yards away and in a heavy sea, imagine the detection you’d get when fishing at your feet. Not so much marginal gains but massive gains.

He moved quickly and with modifications here and there soon had the ideal set-up. He and a few friends — I was lucky to be one — used this style to target mightily impressive grayling on two rivers famous for their big fish, the Tweed and Teviot.

The set-up

The original braid Paul used was bright orange Magic Marker made by Fox for carp-fishers. He wrapped it around a bottle and coloured the braid on one side of the bottle with permanent marker, so it appeared banded — great for take detection. Some 20ft-25ft of it was attached to the fly-line and then barrel-knotted to 3ft of dull olive 016.mm Spiderwire braid. The reason for attaching the Spiderwire was that while the Magic Maker braid and its banding were easily visible, it was too thick to attach a tippet ring. To the small tippet ring, Paul added 4ft of 4lb-5lb (0.14mm) fluorocarbon tippet.

Today, you can get braid especially made for this style of fishing. Wychwood Bugging Braid is thin, strong, and bright yellow. It has 2in black indicator sections. Being bright with black banding it stands out against all backgrounds and is thin enough to attach straight to the tippet ring.

Twenty years ago, there were few specialist fly-rods to match the technique. I used a 10ft five-weight, a heavy hitter compared to the 10ft two-weight I use today. However, it worked. I needed a softish action; too stiff and I might be snapped off on each strike. Rods with through actions (Greys Missionary springs to mind) were ideal as they offered protection in the strike and were exceedingly good at playing big grayling. The giants of the Tweed and Teviot, with their sail-like dorsal fins, know how to use heavy flows to throw a hook. As well as their size, they seem to spend as much time out of the water as they do in it. It’s quite an experience, I can assure you, watching a 3lb grayling leaping out of the water as it heads downstream, peeling line off your reel and making the drag sing as snow falls all around. Great times.

Tippet length, fly spacing and fly position

Diagram 1: Czech nymphing set-up with braid

Diagram 1: Czech nymphing set-up with braid

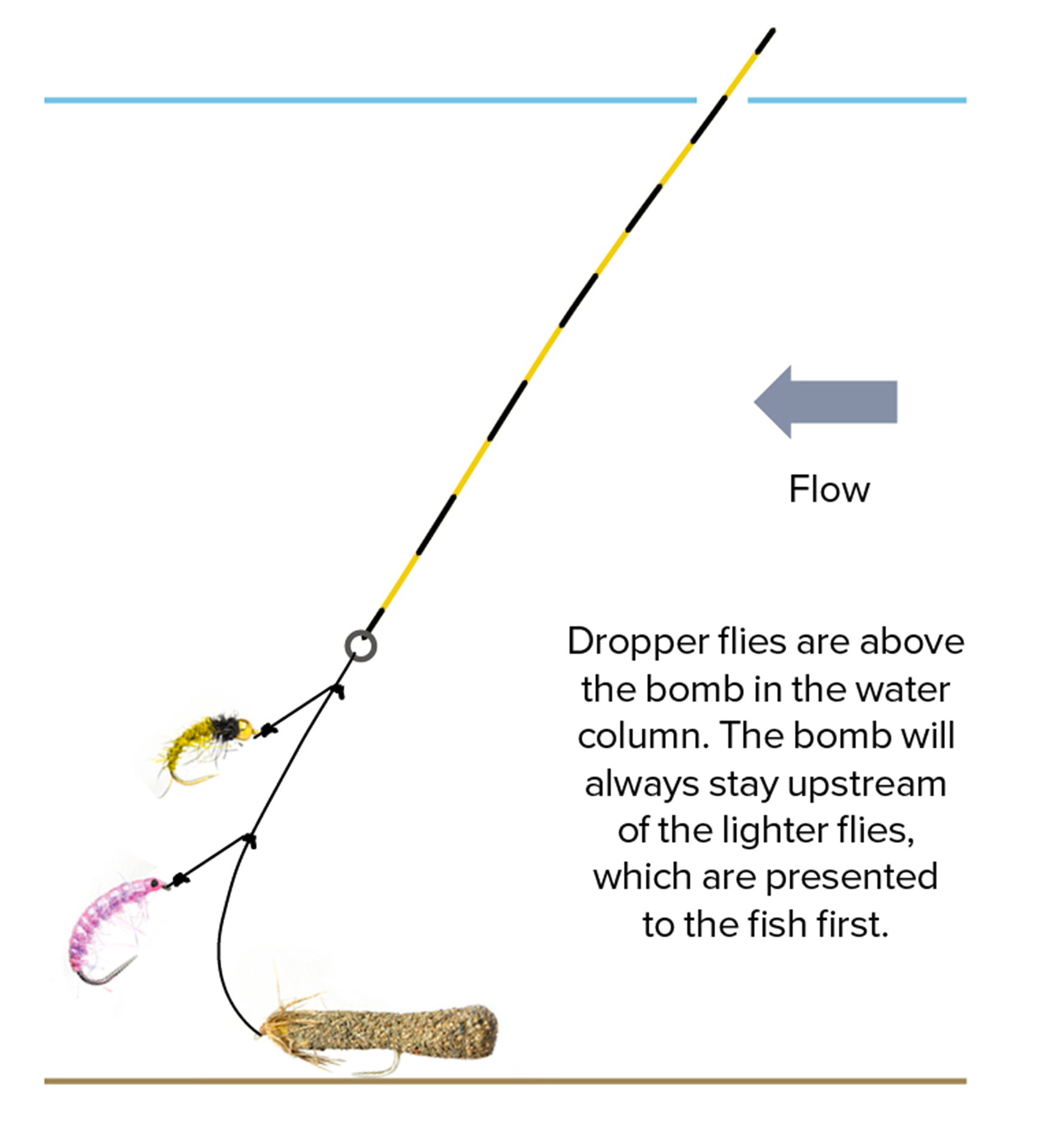

Don’t over-complicate things. My fluorocarbon tippet is short, often only 4ft, or up to the bottom of my chest in old money. Because I am using low-stretch braid I use a strongish tippet of around 0.14mm (4½lb). 0.12mm is as fine as I would go in fear of snapping off. My first dropper (I always fish three flies) is 8in from the tippet ring. The dropper is short, 3in-4in, to avoid tangling. It’s 20in to the next dropper, again short, so there’s little play or slack, and the same again to my point fly. I tend to use the heaviest fly or “bomb” in the point position as it anchors the other flies where I want them in the water column.

Diagram 2: Bomb on the point

Diagram 2: Bomb on the point

For the braid set-up, there’s little difference to standard/original bugging. All we’ve done is replaced the fly-line, a short leader and/or indicator section with braid to heighten sensitivity. Fly spacing is much the same, too. There are about 20in between my flies (50cm is the minimum allowed between knots in river competition rules).

As with standard bugging, to get all the flies deep I must fish the heaviest fly on the bottom, which pulls the other flies lower in the water column.

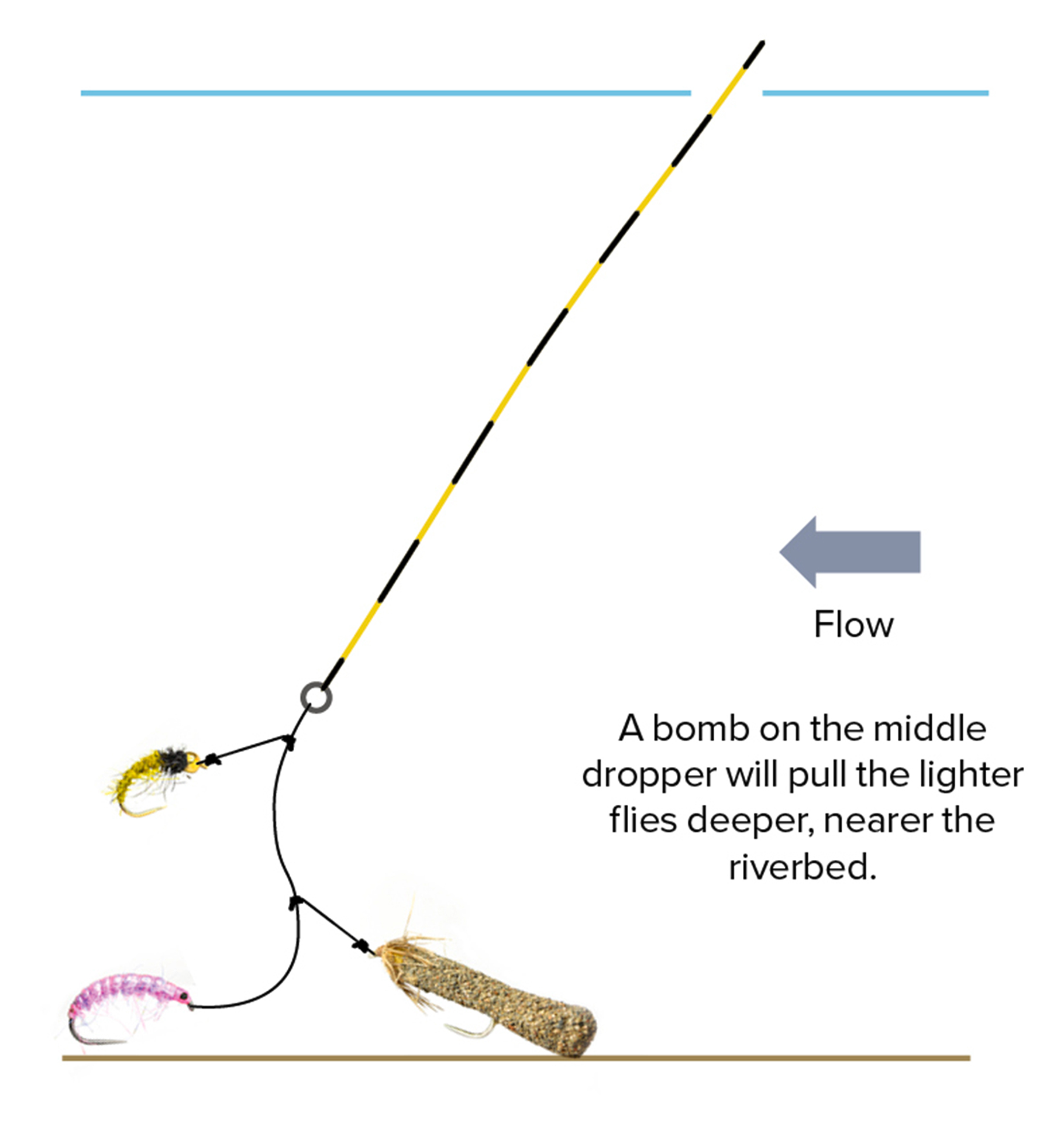

When I want all my flies much closer to the riverbed, I prefer the heaviest fly on the middle dropper as it pulls the lighter flies even deeper and results in fewer tangles than if I placed it on the top dropper.

Diagram 3: Bomb on the middle dropper

Diagram 3: Bomb on the middle dropper

Four flies to try

Clockwise from top: Cased Caddis Bomb, bead-head nymph, Pink Shrimp and Bomb.

Feel your way

To get the most from braid, you can allow flies to drift naturally with the flow, but if you are using heavy beaded flies they can get stuck in the riverbed. Leading your weighted flies downstream with the help of the rod tip will avoid this and keep the flies on the move. A good way to do this is to note a bubble on the water’s surface near where your braid enters the water and track it downstream, or you can move the rod tip so that your line moves a little quicker than the bubble (leading your flies). These are effective methods, but there is a better way.

The bomb is the key. In the past it was sacrificial and never really caught fish, but modern flies fitted with 5.5mm beads and jig-backs can often deliver. The bomb needs to hit the riverbed in a heartbeat so the other flies are fishing straight away. The idea is to feel the bottom through the braid. Trust me, with the right amount of weight this is easy, even in heavy water.

You will feel the heavyweight nymph trundle along the riverbed. It rattles and knocks as you lead it downstream. You must lead it or it will get snagged. I use light-wire hooks for the bomb in case it gets snagged — I can then more easily pull it free.

Steve feels every rattle in his fingers, his eyes looking for movement of the yellow/black bands of braid.

Steve feels every rattle in his fingers, his eyes looking for movement of the yellow/black bands of braid.

The rattling is constant, and you will quickly get into the swing of things. When the rattling stops, you have a take, a fish has inhaled your nymph and lifted the heavyweight point fly from the bottom. This loss of feeling is the time to strike. Only don’t “strike”. Instead, flick your wrist about 4in and that will move the rod tip about 2ft, and pull the hook home. This is often met with solid resistance before the rod tip comes to life as the grayling realises it’s hooked.

The other kind of take is unmissable, when the fish feels the weight immediately and shoots downstream, the heavyweight fly acting like a bolt rig, pulling the small barbless hook home. Hence the need for a soft-actioned rod — the way it yields can prove crucial.

Having used this method for more than 20 years, I am convinced it makes a big difference. I’ve fished a fair few England Eliminators on the Welsh Dee, usually in winter. Faced with water that may have been nymphed three times before I turn up, by gifted river anglers, I’ve used braid. Following these top-notch anglers, you need watercraft and guile, but I’ve done well because my braid leader has much more feel than any other material and no stretch. Not only can I rely on it in heavy flows, in water where a grayling can take and reject a fly without your noticing, but it allows you to connect with fish on almost every take. It’s an advantage and any advantage should be taken.

| Benefits of braid |

■ It’s a thin material and cuts through the water easily

■ No stretch whatsoever compared to normal tippet materials

■ Easy to construct without complicated tippet recipes

■ Allows you to feel flies throughout the drift

■ Can be coloured with a black marker to create banding, helping you to detect takes

■ Great in coloured water or heavy, powerful flows. |

| Drawbacks |

■ When it’s too windy you’ll get a bow in the braid

■ Accuracy is difficult due to the light, thin nature of the material

■ No good on chalkstreams and sight-fishing situations due to its bright colour

■ Tends to wrap around the rod tip. |

Discover the latest tactics from the UK's leading fly-fishers every month in Trout & Salmon magazine. Subscribe or buy single issues here